June 01, 2017

Come into the Garden, Maud?

EDITOR’S NOTE: The author is a retired professor of English at Bryant University in Smithfield, R.I. He lives in Fort Myers, Fla.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Have you ever spent any time at a nearby library reading old issues of your local newspaper? This kind of dillydallying tends to stir up things from your younger years that you’ve almost forgotten. What follows was sired in a sense by some reference-room reading I did recently. It’s an account of a trip to the NIT, the national men’s basketball tournament, in New York City during the spring of 1963 — one that began in the old parking lot between Harkins Hall and Alumni Hall on the Providence College campus, and one that turned out being sort of a blue-green weekend of gaffes, games, girls, and laughs.

The seven of us had decided to cut our Friday afternoon classes to see PC play Marquette in a doubleheader at Madison Square Garden, one that started at 7:30 p.m. The National Invitational Tournament — the oldest post-season college tourney in the land — was in its 26th year then and was still prestigious. This was PC’s fifth consecutive appearance in it; quite an accomplishment for a school with only 3,000 students. So around noon we piled into my 1960 Ford, a black-and-white Fairlane with fins on the stern, and headed off towards Route 6 and the Connecticut Turnpike beyond. All of us — Andy, Bernie, Chad, Eddie, Henry, “Space,” and me — were commuters from Providence and Pawtucket and were avid basketball fans. We expected to reach the Big Apple by 4 o’clock but anticipated slushy roads. Three inches of snow had fallen on Thursday. The forecast for the weekend was promising, however: “Crisp and clear with daytime temperatures in the forties.”

Actually, five of us — Andy, Bernie, Eddie, Space” and me — were going down for the rest of the tournament. Certain that the Friars would reach the Saturday afternoon final, we had booked a reasonably-priced room for two at the Taft Hotel on Seventh Avenue — a block over from the ol’ Garden. Visions of post-St. Patrick’s Day celebrations danced in our heads. The last week of exams and papers had been grueling. As for Chad and Henry, the other two sophomores with us, they were along for the day only. On restricted funds, they were getting a “red eye” at Penn Station after midnight — one which would bring them back to Rhode Island before daybreak.

Once our juggernaut got into Connecticut the slush started to disappear. The biggest hurdle ahead of us looked like it would be rush-hour traffic in Gotham, which we’d be encountering en route to the MSG Box Office. We were picking up our tickets right away to avoid long lines later. Near Exit 85 Chad said, “Turn-up the heat.” Sheepishly I replied, “My heater doesn’t work too well. Perhaps you should put out your cigarette and close your window. Then you’ll be warm enough.” With my blue blazer on, I wasn’t cold. “OK,” said Chad, a suave sociology major dressed in khaki slacks and a gray turtleneck pullover. “I’ll close my window as soon as I’m done with this — it’s my last one.” “Hurry up,” said “Space,” an erudite economics major attired in a Boston Red Sox cap and a cranberry sports jacket.

Space was sitting by the other rear window. Like the rest of us, he was a non-smoker who considered some of the habits of smokers distasteful. Between Chad and Space sat Henry and Eddie. For these four six-footers in back, the seating was snug. Henry had to sit on Eddie’s lap and Space had to contend with two items which wouldn’t fit into my trunk — Bernie’s coat and suitcase. “Too bad we couldn’t get tickets on campus,” said Andy, a temperamental history major wearing a green beret and Boston Celtics sweatshirt, as Chad took his last puff and closed his window. It had been open a few inches but hadn’t bothered Henry or Eddie for some reason. “Look at it this way, some things done at the last minute turn out well,” I answered.

Then we started discussing basketball. “Do you think PC should have been invited to the NCAA Tournament?” asked Bernie, a short, spunky political science major who had gone to the same high school as I and had been a dedicated Kennedy volunteer three years earlier. He was sitting next to me. “After all,” said Bernie, “the team has a 21-4 record, was ranked 10th in the country by the AP recently, and just ended the regular season with 12 victories in a row, the best winning streak in school history.” I responded, “Perhaps they should have gotten an NCAA bid but only 25 teams get into that tournament and most are conference champions. It’s tough for an independent.” “I think PC would’ve been competitive in the NCAAs,” said Andy from his front-seat berth next to the passenger window. “Vinnie Ernst is the greatest little point guard in America, and Jim Stone is the best one-legged player in basketball.” Ernst had been MVP of Providence’s 1961 NIT Championship team. Stone, a transfer from Grambling, played on a screwed-up knee — one which made most of his shots look like the tricks of a contortionist. In January, he had quit the team briefly because of his chronic knee problem.

As we approached Old Saybrook, Henry asked me if I had seen Tuesday’s Providence College-Miami of Florida NIT quarterfinal game on Channel 12. Because PC had received an opening-round bye, it had been its first tournament game. “Yeah,” I said. “PC turned the Hurricanes into a squall. The final score was 106-96.” “I caught some of Chris Clark’s radio broadcast while working on an assignment for my 8 a.m. Latin class,” replied Henry.

Like me, Henry was an English major who had to take a year of Latin. He was wearing a white fisherman’s sweater and blue slacks. “I missed the end of the game,” added Henry. “What time did it get over? asked Eddie, a lanky business administration major from Pawtucket. “Close to midnight,” I replied. “Were any of you surprised that Joe Mullaney decided to run with Miami?” asked Andy. The Friars’ mentor, Mullaney was a defensive strategist who tended to eschew an up-tempo style of play. Later he coached for six years in the NBA and ABA, two of them with the Los Angeles Lakers. Several of us indicated we were surprised. “How many points did Flynn, Stone, and Thompson get?” asked Chad. Like Henry, he had not heard the whole game. I answered, “Ray Flynn had 38, Jim Stone had 26, and John Thompson had 17. Flynn, a 6-foot guard from South Boston, was the team’s captain and long-range sharpshooter; Stone, a 6-foot-2 leaper from Cleveland, was one of the versatile forwards; Thompson, from D.C., was the team’s 6-foot-11 center. “How many assists did Vinnie Ernst have?” asked Henry. “Eleven,” replied Bernie. From Jersey City, N.J., the 5-foot-8 Ernst was the “glue” that held the Friars together. He was a superlative playmaker. “PC did a good job on Barry,” said Eddie. Also from New Jersey, Rick Barry was held to 14 points that evening. The talented Miami sophomore had been averaging 19 per game.

When we reached New Haven, we were still talking basketball sporadically. Andy asked, “Who has had a better career at PC? Johnny Egan or Vinnie Ernst?” A Hartford native, Egan was a 1961 graduate; Ernst was presently a senior. Egan’s artifice in bringing a basketball around his back while on his way to the basket and in mid-air had led to his acquiring the nickname “Space.” Later, he played for 10 years in the NBA, two of which were with West, Baylor, and Chamberlain on the Lakers. The “Spaceman” traveling with us had the same name so we called him “Space” too.

An unscheduled stop

“Do you think Vinnie will play tonight?” asked Eddie. Ernst had pulled a hamstring muscle behind his right knee in the Miami game on Tuesday and was a doubtful starter. “I don’t know,” said Andy, “but PC is in trouble without him.” This kind of Thomistic talk continued until somewhere south of the Bridgeport tollbooth. It was then that I spotted flashing lights in my rearview mirror — those of a Connecticut state trooper! I pulled over, and he pulled up behind me. After taking my license and registration, he went back to his car. Moments later he approached my window again and asked, “Hugh, where are you going in such a hurry?” I answered, “Officer, we are Providence College students on our way to a basketball tournament in New York.” Frowning for a moment, he said, “Do you know you were just going 70?” I replied, “No, I wasn’t aware of that, Officer. Everyone in here’s been talking. The chatter may have distracted me.” He looked around at all of us and said, “OK, but slow down!” Without another word, he returned to his patrol car and drove off.

We continued on our way and did not stop again until we reached NYC. By 4:30 p.m., we were outside Madison Square Garden but with nowhere to park. Eventually, we found a metered space on 50th Street. Chad said he’d stay with the car; the rest of us went off hastily for our tickets. Not long after we’d gone, Chad decided he needed cigarettes. He had seen a grocery store nearby. When we came back, Chad was puffing on a Lucky Strike and looking contrite. He told us, “Someone has stolen Bernie’s coat and suitcase. They were heisted in the blink of an eye. I was only gone ten minutes — had to get some smokes.”

Subsequently, six of us set off in search of a police station to report the loss. Andy stayed with the car. Not far from our meter we found a shabby and dilapidated NYPD station house, one bustling with activity. What transpired there is a little fuzzy. As I recall, we spoke to a mild-mannered minion of the law named Sergeant Clapp. He had Chad describe the scene of the crime and Bernie describe the purloined belongings. Chad explained how Bernie’s things vanished in broad daylight without any signs of a break-in. Bernie explained how his new winter coat and nearly new suitcase — a dark green Navigator and a tan American Tourister — were Christmas and birthday presents from his parents and sister. Then Bernie filled out a police report and got a copy of it for his insurance company. As we were leaving the station, Bernie exclaimed, “I’ll take the train home tonight with Chad and Henry. I can’t stay over without any clothes.” When we reached the car, we had two hours till tap-off to register for our room and get a pre-game bite. So we hurried along. Soon the seven of us were out hoofing for hamburgers. Near the Port Authority Bus Terminal we entered a White Tower.

Because Providence had one of these restaurants, we knew we’d get fast service there. The familiar sign over the building’s exterior of porcelain enamel panels was reassuring: HAMBURGERS: BUY A BAGFULL. Inside, we saw that the seven stools at the counter were taken but that two of the five booths along the front window were not. We sat down, scanned the menus, and looked around. The white walls and counter were as clean as a whistle. Behind the counter were several display cases containing pies and cakes. Above these was a round clock. On the wall near the door was a black pay phone. Next to it was a large calendar set on March, the top portion of which had a colorful picture of Blarney Castle. Someone had circled the 22. Hanging from the ceiling were a number of large light fixtures — translucent globes like those you used to see in schools. Most of the customers looked like weary New Yorkers.

A petite “Towerette” named Dawn came over to take our orders. She was wearing a little white cap, a polka-dot dress, and a faded apron. The top buttons of her dress were undone. Next to her name tag was a Smiley button. With aplomb, we ordered hamburgers, fries, and Cokes all around. Except Chad. He wanted a coffee. All of us said we’d have onions on our hamburgers. Except Bernie. He wanted one with lettuce, tomato, mayonnaise, and extra mustard. Ten minutes later, our cuisine arrived. We attacked it like zealots. All of us were famished. Suddenly, Bernie shouted, “There’s no hamburger in my bun.” One bite had augured an absent patty. While heads turned and people stared, Dawn walked up to Bernie and chirped, “What’s amiss?” She was unperturbed. Bernie showed her what was wrong and said, “Could you take this bogus burger back to the cook and bring me a replacement? With a bird-like nod, she did and didn’t say a word. Bernie ate the new one amidst a stream of guffaws from the rest of us.

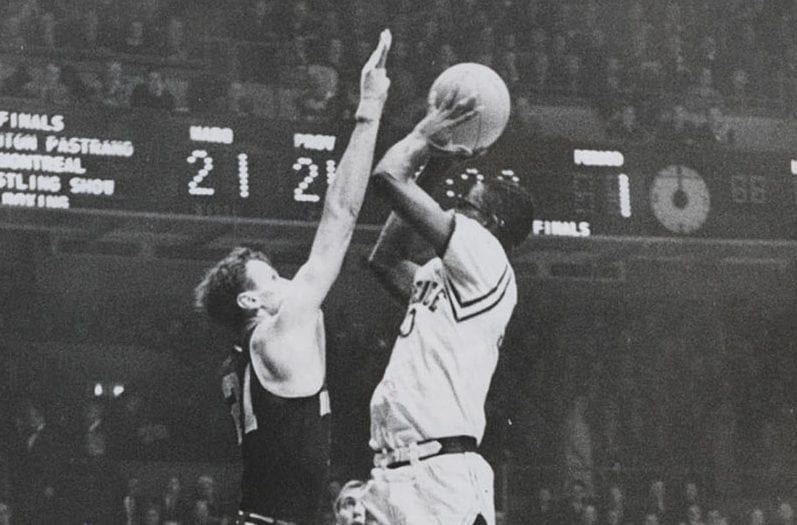

Afterwards, we had some dessert, left Dawn a $2 tip, and took off. It didn’t take us long to reach Madison Square Garden, outside of which Bernie sold his ticket for Saturday. When we went inside, we located our upper-tier seats, watched the Friars warm up in their white “home” uniforms, and listened to the PC band strike up “When the Saints Go Marching In.” Then we heard the introductions of the players. Surprisingly, Vinnie Ernst started — albeit with a knee brace. Eventually, it was apparent that the game would not be a high-scoring affair. Each team was playing tough defense. Marquette held Ray Flynn to eight points in the first half, one in which both the Friars and Warriors struggled offensively. At halftime, it was Providence 32 and Marquette 25.

In the second half, Flynn was hot, making eight spectacular long-range shots. John Thompson guarded the PC basket like a lumberjack and blocked four Marquette attempts. Vinnie Ernst played another superb floor game and hit four straight free throws in the final minutes. When the game ended, four PC players were in double figures: Flynn had 25 points; Stone had 15; Thompson had 12; and Ernst had 12. Six of Stone’s points were the result of twisting lay-ups on his good leg. Thompson amassed 16 rebounds. Flynn shot 50 percent for the game. Three Marquette players hit double figures. Several exciting situations occurred during the game’s hectic finish. The final score was Providence 70 and Marquette 64. Moments before the end, the Jersey Skeeter departed to a thunderous ovation from the 18,429 fans in attendance, over 3,000 of whom were Rhode Islanders. In the nightcap, Canisius beat Villanova soundly by a score of 61 to 46. This set up a Providence College-Canisius final the next day at 4. We left with a half-hour to go in the second half of the second game and walked over to Times Square, where Bernie, Chad, and Henry split to get their train.

Rhode Island meets Boston in NYC

After wandering around for a while, the four of us — Andy, Eddie, Space, and me — spent half an hour outside the Peppermint Lounge on West 45th Street looking at familiar faces, wondering what was happening at the Friday-night mixer back in Harkins Hall, and listening to some loud rock. Inside, Joey Dee and the Starlighters were performing a series of songs with a twist. Their hit, “The Peppermint Twist,” had recently soared to number 5 on the pop charts and was extending the national craze started by Chubby Checker three years earlier. Then we went back to the Taft to our room on the seventh floor. A throng of tourists was in the corridor. We weren’t in our room long when Space noticed a note under our door. He picked it up and read it to us: “WOULD YOU LIKE TO MEET SOME GIRLS FROM BOSTON? IF SO, KNOCK ON ROOM 734.” We were staying two doors down.

Within minutes we were at their door. A wiry redhead in purple slacks and a pink sweater let us into their room, one which looked like ours. It had two double beds, a chair, a picture of a carousel in Copenhagen on the wall, and buff carpeting. The redhead said her name was Claire and introduced us to the two girls with her, Bonnie and Audrey. Claire told us that Bonnie and she were from Needham and that Audrey was from Natick. Bonnie was a brunette dressed in turquoise slacks and a tight aquamarine sweater. Audrey was a slender strawberry blonde with soft green eyes and a lovely smile. She was wearing a beige corduroy skirt and a brown cashmere sweater. “All three of us are freshmen at Boston University,” announced Claire. “We’re sophomores at Providence College and are from Providence and Pawtucket, Rhode Island,” responded “Space.” He was the one who’d knocked on the girls’ door. “We’re here for the NIT at Madison Square Garden. We saw PC beat Marquette tonight in a great game. Tomorrow we play Canisius for the championship.”

“How long have you been here?” we asked. “We’ve been here all week,” said Claire. “We’re on spring break. Tonight we went bowling across the street. Don’t try it. The place is crawling with creeps. We saw you guys in the hallway on our way back and heard you talking about the game. Are you going to do any sightseeing here?” “No,” I replied. “We got here today and are leaving Sunday.” “We’ve done a lot of sightseeing,” said Bonnie, who looked older than a freshman. “Would you like something to drink?” “Yes,” we said. Claire went over to the night table between the beds and poured glasses of wine for the four of us. The girls had provisioned the place with an ample supply of Coke, wine, cheese, crackers, and potato chips. “Help yourselves to some cheese and crackers or chips,” said Bonnie. “Thanks,” we replied. “How long are you here ’til?” asked Eddie. “We’re checking out tomorrow,” responded Bonnie. “We’re taking a bus back to Boston at noon.” Then Eddie and Space started talking to Claire and Bonnie on one side of the room, while Andy and I began to speak to Audrey on the other. Searching for something clever to say, I asked Audrey, “What are you majoring in at BU?” “English,” she replied. “So am I,” I said. “Where is Natick?” asked Andy. “West of Boston — off Route 9,” replied Audrey in a gentle voice.

“Have you been to any plays here, Audrey?” I asked in an attempt to keep the conversation on a literary track. “Last night we went to the Majestic Theatre on Broadway to see Sheridan’s The School for Scandal,” said Audrey. “Did you like it?” I asked. “It was OK, but it had a disjointed plot. Wednesday night we saw The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm at a Cinerama Theatre not far from here. The screen in there was huge.” Cinerama Theatres were ones which utilized three synchronized projectors and multi-track stereo sound to show their widescreen features. Popular for a few years in the early ’60s, Cinerama was a precursor of IMAX and OMNIMAX. “What’s Wonderful World about? I asked. “It’s an account of the lives of the German fairy tale writers and a dramatization of three of their tales,” answered Audrey. “I’ve seen ads for it. It’s also playing in Providence at a Cinerama Theater on Hope Street.” When Andy went to get some cheese and crackers, I asked Audrey about their sightseeing. She told me, “We took a Gray Line tour of Manhattan on Monday, one which went to the Statue of Liberty, and have seen several things since. We’ve been through Radio City Music Hall, The Cloisters, Rockefeller Center, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Empire State Building, and the American Museum of Natural History. The weather has been horrible. Yesterday afternoon we saw a show called Stories in the Stars at the Hayden Planetarium. Bonnie is a biology major and Claire is majoring in art.”

Afterwards, Andy sat down sullenly beside the others. Subsequently, I asked Audrey if she’d ever been to the Museum of Science in Boston. When she said that she had, I mentioned how I had been there the previous March when my high school science project on “Hydroelectric Power from the Sea” won a first grant at the Rhode Island Science Fair and was selected for the 1962 New England Science Fair at the Museum of Science. “How long did you stay in Boston?” asked Audrey, who seemed sanguine, yet shy. “Three days,” I answered. “The sponsors paid for all of my expenses. I had a great time.” “How did you get the idea for your project?” “On a camping trip to Fundy National Park in New Brunswick during which we visited an area called the “Flower Pots” on Hopewell Cape and witnessed the awesomeness of the tides in the Bay of Fundy. They are some of the highest in the world.” “Did you tour any power plants while you were there?” “No.” “My brother would enjoy talking to you. He has a Ph.D. in physics from MIT and works in Lexington for Lincoln Laboratory, a research and development firm which advises and assists NASA. Did you see John Glenn become the first American to orbit the earth last year?” “Yes.” “I was at Cape Canaveral for the launch. My brother worked on some of the communications systems for Friendship 7, the Project Mercury capsule which carried Colonel Glenn around the world three times. It was exciting.

“Anyway, which do you prefer — English literature or American literature?” “English lit.” “I like nineteenth-century American literature. Have you ever been to Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord?” “No.” “Hawthorne, Emerson, the Alcotts, and Thoreau are buried there. It’s worth visiting.” “Have you ever read the poem “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” Audrey?” “I don’t think so.” “W. B. Yeats got the idea for it from a passage in Walden. “Where is Innisfree?” “It’s in Sligo, a seaport and county seat in northwestern Ireland. Some of my ancestors come from there. My great-grandfather built the Sligo Cathedral. My mother was born in Dromahair, a bucolic village a few miles away. She and her nine sisters and brothers grew up in a barracks. Her father was an Irish constable.” “Where’s your father from?” “He was born in Darwen, an industrial town in the Midlands of England.” “How did your parents meet?” “At a St. Patrick’s Day dance in Providence. They came over here in their twenties.” After telling me a few things about her parents, both of whom were from Massachusetts, Audrey asked me if I liked folk music. When I said I did, she wanted to know who my favorite folk singers were. I told her I liked Joan Baez, the Kingston Trio, and Peter, Paul, and Mary. For a few years in the early ’60s, everyone was listening to these troubadours. “I have P, P, and M’s two LPs,” remarked Audrey. “I just bought their second one. I like Joan Baez, too. Did you know that her father is a professor of physics at MIT?” “No.” “Did you see her at the Newport Folk Festival two summers ago?” “Yes. She was great. So was Peter Yarrow.”

Favorite shows and animals

A little later Audrey asked me if I’d like another glass of wine. I said, “Sure.” While she was getting us some, I overheard Claire questioning the others about their favorite TV shows. Eddie told her his was Saturday’s The Defenders with E.G. Marshall and Robert Reed. It was a show about father-and-son lawyers. Andy said his was Tuesday’s The Untouchables with Robert Stack. It was a Prohibition-era crime drama with a documentary style. Space told her his was Wednesday’s Naked City with Paul Burke. It was a tough-edged police series. Bonnie said hers was Monday’s Ben Casey with Vince Edwards. It dealt with the doings of a surly but gifted surgeon. Then Claire said hers was Thursday’s Dr. Kildare with Richard Chamberlain and Raymond Massey. It was a medical series, too.

When Audrey returned with our wine, she mentioned that she had a 3-year-old poodle named Bonkers and asked me if we had a dog. I told her we had a 4-year-old Cocker Spaniel named Brownie. “We bought our black Standard Poodle from a kennel in Braintree,” said Audrey. “He’s docile but daffy: When he’s in the house he stalks sunbeams and barks at dogs on TV; when we take him out for walks he tries to chase cars; and when we tie him outside he digs holes in our yard.” “Does Bonkers like popcorn?” I asked. “No.” “Brownie loves it. We throw pieces to her while we’re watching TV, and she catches them like a major leaguer.” “Does she like balls?” “Yes. Even basketballs. When I’m shooting hoops in my driveway, she guards me tenaciously and tries to steal the ball from me. She’s also fond of acorns. Last fall she had two operations because of acorns she ate. We have a large oak tree in our backyard, one from which acorns have been falling in droves. In October, our vet had to cut open Brownie’s stomach twice to remove two of them.” “Two operations?” “Yes. A week after swallowing the first acorn, she ate another one. It had to be taken out of her intestines also. The surgery was expensive. “Guess what? There are no acorns in our yard now.”

“Do you have any other pets, Hugh?” “Yes. We have a spasmodic parakeet named Maude. She’s a dilly.” “Really? We have a canary called Hester. She’s a honey.” “Can Hester talk?” “No.” “Maude can. When my mother lets him out of his cage for an occasional spin around the house, he sits on our windowsills watching the birds outside and talks up a storm.” “How long have you had him?” “Two weeks. We got him from my Aunt Maude. She lives in Marblehead. After teaching the green-feathered gremlin to say something, she decided to disown him.” ”Why?” “He drove her nuts by repeating relentlessly a line from Tennyson’s long poem, Maud.” “What’s the line?” “Come into the Garden, Maud?” “Does the repetition of the line bother your parents?” “My father doesn’t mind it, but my mother does. She’s trying to teach her something Irish.” “Who gave the Victorian scholar her name?” With a wink almost as large as a whale, I answered: “My aunt!” Afterwards, I asked Audrey if her parents had voted for JFK in 1960. When she said that they had, I told her how my mother had composed a tune for his presidential campaign during the summer of 1960. About this I crowed: “Although his staff didn’t use the song, John Kennedy sent my mom a nice acknowledgment the following September — one from his headquarters on Connecticut Avenue in the District of Columbia.”

Around 2 a.m., Audrey suddenly murmured: “Would you like to go to your room, Hugh? It’s getting noisy in here.” Two sets of thoughts sprang into my mind. The first contained these reflections: What will Audrey and I do while we’re alone? Am I ready for what could occur? Did anyone see the seven of us going into our room earlier? Have any of the guests complained about our talking? What if Hotel Security checks on us? Were overcrowded rooms for the 1961 NIT really raided? Has Sarah seasoned me for this? Would humming a few lines of “Mary Plead for Me with Jesus” help? The second set of thoughts contained these reflections: Do I want to be secluded in a hotel room with a girl I just met? Perhaps! What will happen? Saturation sex! Were the seven of us seen earlier? Maybe! Have there been any complaints? Maybe! Will Security check on us? Possibly! What kind of high-school heartthrob was Sarah? Seraphic! Did that first-year postulant at Mount St. Mary’s season me? Not really! How about “Mary Plead for Me with Jesus?” Was I wondering about this hymn of my mother’s because she played it on our organ constantly, because the publisher of it was a firm in New York City, or because of something else? Humming a line of it might help! After dwelling on these thoughts briefly, I gazed into Audrey’s green eyes and replied, “I don’t think that’s a good idea, Audrey. The room isn’t registered in my name.” “OK,” said Audrey, who then remarked, “Excuse me for a few minutes. I’m going to get ready for bed.”

When she came out of their bathroom, enigmatic Audrey was wearing a pair of yellow silk pajamas — ones which accentuated her strawberry blonde hair and looked great on her. As she crawled under the covers, she commented, “I got these on sale at Jordan Marsh last week. Sit over here so we can continue talking.” After I sat down beside her on the edge of the bed, I asked her to tell me about her tour of Radio City Music Hall. She said that the art deco landmark was the world’s largest theatre — one with a stage as wide as a city block, an enormous organ called the Mighty Wurlitzer, a magnificent mural called Fountain of Youth, and three notable pieces of sculpture: Eve, Dancing Girl, and Goose Girl, all nudes. Continued Audrey, “I think the latter is based on a fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm. In their Goose Girl, a passive princess betrothed to the son of a distant king has to perform the common duties of a goose girl after being betrayed on her journey by a false waiting maid. The servant takes the princess’ talking horse, exchanges clothes with her, impersonates her, and has her trusty steed decapitated so he won’t reveal what has happened. Then she marries the expectant prince. However, the king hears goose girl conversing with the head of her dead horse. It hangs over a gateway through which she passes daily. This enables the old king to realize what has occurred. Eventually, he executes the perfidious maid and has his son marry the true princess.” “Wow! That’s quite a tale.

“What did you see at The Cloisters, Audrey?” “We saw several pieces of medieval architecture and art.” “Why is the place called The Cloisters?” “Because the medieval-style building incorporates original sections of 12th-to-15th-century French monasteries. A cloister is an open courtyard with a covered and arcaded passageway along the sides. In western European monasteries the most important buildings were grouped around a central cloister.” “Where is The Cloisters?” “It’s in Upper Manhattan, overlooking the Hudson.” “What did you like best there?” “The Unicorn Tapestries, a set of seven Flemish wall hangings which were woven in the 15th and 16th centuries and which depict the Hunt of the Unicorn. They mingle Christian allegory, pageantry, popular legend, and flora and fauna associated with courtly love and are displayed in a replica of a nobleman’s hall.” “What’s a unicorn?” “It’s a swift and powerful mythical white beast with the body and head of a horse, the hind legs of a stag, the tail of a lion, and a horn in the middle of its forehead. According to legend, it is captured when it rests its head on the lap of a lady. Subsequently, it is slain by a hunter. However, in the seventh tapestry the unicorn reappears alone and alive. He’s in a wooden enclosure and is leashed to a pomegranate tree.” “Who made the tapestries?” “No one knows.

A shift to recent reads

“Anyway, what have you read recently, Hugh?” “I just finished Cecil Woodham-Smith’s The Great Hunger. It’s an account of the famine which devastated Ireland in the 1840s and of the British government’s response to it. My father had me read it. His ancestors were famine emigrants. They settled in Lancashire in 1846. “When was the book published?” “Last year.” “What caused the famine?” “A fungus destroyed the potato crop sustaining the peasants of Ireland. The blight turned Irish fields black overnight. The people who perished died of starvation and disease.” “How many died?” “Over 2½ million.” “Did the Irish receive any aid from England?” “Not much. The British government’s scheme was relief through employment, a strategy which was ineffective. The concept of laissez faire prevailed. During the first phase of the famine, the British demonstrated some generosity, but during the second phase their policies approached genocide. Huge quantities of food were exported from Ireland to England in the mid-1840s, and no effort was made to teach the Irish people how to grow another crop or improve their methods of agriculture.”

“What else have you read lately?” “In January, I read John Knowles’ A Separate Peace, which deals with a boy’s betrayal of his best friend at an Edenic prep school in New Hampshire during World War II. It’s a short novel, but one which has won a couple of awards.” “Is it new?” “It was published in 1960.” “What kind of boys are they?” “They’re 16-year-old roommates at a prestigious place called The Devon School and are from somewhere in Dixie and somewhere outside of Boston. One is named Gene and the other is named Finny. The two are similar in stature but opposites otherwise: Gene is a superior student, while Finny is an excellent athlete. Gene tutors Finny in Latin, while Finny tutors Gene in track. Gene broods over things and is a cautious conformist, while Finny is a spontaneous individualist who has a vitality not easily squelched.” “Which of them is the central character?” “Finny. However, Gene is the narrator. He tells the tale retrospectively, 15 years after graduating from Devon.” “Which of the boys is more memorable?” “Finny, because he’s so whimsical and unconventional. For example, at Devon he invents a game called Blitzball, one for which he creates crazy rules while play is in progress. Also, he breaks the school swimming pool record in the 100-yard freestyle just for the fun of it. Afterwards, he takes a three-hour bike ride to the beach where he displays his fishlike traits by staying in the cold New Hampshire surf for nearly an hour.

“Later, he improvises a wacky Winter Carnival at which he awards peculiar prizes for things like ski jumping on a flat field and organizes screwy snowball fights during which he constantly changes sides.” “So how does Gene betray Finny?” “He causes him to have an accident. This happens at a huge tree on the school campus, one with a limb that extends out over the Devon River. Getting students to spring from this limb into the water below is another of Finny’s flights of fancy. Those Devon students who make the jump belong to the Super Suicide Society of the Summer Session, a club dreamed up by Finny during the summer of 1942. In an early episode, Gene is saved by Finny from falling off the limb. However, in a subsequent incident, one which is the novel’s central episode, Gene shakes the limb and forces Finny to lose his balance. Gene seems to do it on blind impulse. Finny falls onto the bank below and breaks his leg. Later, Finny fractures his leg again on a marble staircase outside the Assembly Room. This happens right after an emotional inquiry into the circumstances surrounding the incident at the tree. At this mock trial a group of Devon students seeks to determine whether Gene was the culprit. That’s enough, Audrey. I don’t want to tell you everything in case you decide to read it.”

“OK, just tell me why the novel is called A Separate Peace?” “Because Gene eventually stops brooding over his betrayal of Finny and makes peace with himself. Then he takes his things from his locker and goes off to fight in World War II. But the war theme does not predominate. Knowles’ novel deals instead with how we all lose something while growing up. It’s worth reading, Audrey.

“Anyway, what have you read recently, Audrey?” “I just finished Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, an account of how we have been destroying our ecological web of life since World War II. Bonnie loaned it to me.” “When was Silent Spring published?” “Last year, after parts of it were serialized in The New Yorker a few months earlier. It’s a best-seller.” “Did Rachel Carson write The Sea Around Us?” “Yes. She’s a marine biologist who spent several summers studying at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory on Cape Cod.” “How serious are the problems discussed by Carson in Silent Spring?” “She believes that pesticides are falling from our skies like rain and are devastating our wildlife and livestock. She claims that some of the major spraying programs of the Agriculture Department have been ill advised, hastily conceived, and poorly planned. She likens how these programs allow our food to be poisoned and then police the result to the White Knight’s plan in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass to dye his whiskers green and then use a fan to keep them from being seen. Over the years, says Carson, we have had extremely expensive efforts to eradicate Dutch elm disease, the gypsy moth, the fire ant, and the Japanese beetle, all of which have failed.”

“Does she believe that some of our chemical programs tend to be self-defeating?” “Yes. She states that often they don’t take account of the complex biological systems against which they are hurled. Believing that the best way to preserve our earth is to take the road less travelled, Carson notes how the proliferation of chemical pesticides has contaminated our soil, water, and food and how this has the potential to make our streams fishless and our gardens and woodlands silent and birdless. She reminds us that all life on our planet is interrelated. She uses two literary quotations to start Silent Spring. Here’s one of them: ‘The sedge is wither’d from the lake, / And no birds sing.’” “That’s from Keats’ ballad La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” What’s the other one?” “It’s from E.B. White and goes something like this: I am pessimistic about the human race because it is too smart for its own good. Our approach to nature involves beating it into submission. Rachel Carson concurs. She’s convinced that we are living in a world where every human being has needless contact with dangerous chemicals from birth ’til death.” “I’ll have to read Silent Spring, Audrey.

“In the meantime, could I use your bathroom?” When I returned from the john, I looked at my watch, saw that it was 3:30, and overheard Bonnie asking Eddie, Space, and Andy if they were skiers. I perked up at this because I had just learned to ski myself. Space and Eddie said they were beginners who did their skiing at Bromley in Vermont. Andy admitted that he wasn’t a skier. Bonnie and Claire said they skied at Gunstock in Laconia, New Hampshire, and were also beginners. “Where’s Bromley?” asked Claire. It’s in southern Vermont, a few miles east of the town of Manchester,” said Eddie. “You’d like it. It has wide beginner slopes, ones that are always sunny when the sun’s out.” “I’ve been to Manchester, to see Hildene, the summer home of Robert Todd Lincoln,” commented Andy. “Has anyone else seen it?” “No,” answered all of them. “Who is Robert Todd Lincoln?” asked Bonnie. “He was the oldest son of Abraham Lincoln,” replied Andy. “After graduating from Harvard, he became secretary of war under President Garfield and U.S. minister to Great Britain under President Benjamin Harrison.” That was all I heard of their conversation.

When I sat down again on the edge of Audrey’s bed, she told me to hang up my jacket and stretch out beside her. This took my mind off what the others were discussing. “Sure,” I told Audrey. While I was removing my jacket, Audrey asked me, “What’s the insignia on the vest pocket of your blazer?” I explained that it was Providence College’s emblem and that the word “Veritas” above it was the College’s motto. Then I lay down next to Audrey — on top of the covers. She was under them. That is, they were up to her waist. As I did, Audrey asked me in a tremulous voice if her hair was messed up. “No, your hair looks fine,” I replied. It wasn’t difficult to see that this was true. Both of us were lying on our sides, with our noses nearly touching. Not only did the recumbent Audrey look radiant but her mellifluent scent of lilacs started mesmerizing me. “In case you’re wondering, this is the natural color of my hair,” noted Audrey.

“Anyway, what good movies have you seen recently, Hugh?” “Two weeks ago I saw To Kill a Mockingbird with Gregory Peck. It was great! Have you seen it?” “No.” “It’s been nominated for several Oscars. You ought to see it.” “What’s it about?” “It deals with race relations in a small town in Alabama at the end of the depression. In it, Gregory Peck plays Atticus Finch, a Southern lawyer who has two mischievous children named Scout and Jem, who lives next door to a strange recluse named Boo Radley, and who defends a blameless black man named Tom Robinson. Six-year-old Scout narrates the story. The plot has two strands to it: one involves the Finch kids’ efforts to lure Boo Radley out of hiding; the other involves an unforgettable trial. I won’t tell you about the trial, however. Doing so would spoil the movie for you.” “Is To Kill a Mockingbird based on a best-selling novel?” “Yes. Harper Lee’s. I’ve read the novel, too. It was published in 1960 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1961.” “Why is it called To Kill a Mockingbird?” “Because references to mockingbirds echo throughout and because there are two scenes in which the Finch kids are told not to hurt them. In one, the kids’ aunt, Miss Maudie, reminds Scout and Jem that mockingbirds make sweet music and sing their hearts out for people. In another, Scout tells Atticus that sending gentle Boo Radley to jail would be like killing a mockingbird. By the way, one of Scout’s friends, a boy name Dill, is supposedly based on Truman Capote. Capote was Harper Lee’s childhood companion in some small town in rural Alabama.

“Really? Did you see last year’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which stars Audrey Hepburn and is based on a novella by Truman Capote?” “No. What’s it about?” “It deals with a 19-year-old New Yorker named “Holly” Golightly who lives a lonely life in her Manhattan brownstone, who keeps her phone in a suitcase so its ringing won’t bother her, who gets the “reds” (rather than the “blues”), and who crosses her heart and kisses her elbow for good luck. When she goes out, she wears a large, stunning black hat. At Tiffany’s, she has a ring from a box of Crackerjacks engraved for $10.” “Does Holly work or go to school?” “Neither. She gets along by making weekly visits to the jail cell of a convicted Mafia figure named “Sally” Tomato. At a place called Hamburg Heaven, Holly had agreed to cheer up the convict for a hundred a week. After each of her visits to Sally at Sing Sing, Holly leaves verbally coded messages on the answering machine of the convict’s lawyer … ones which seem to be merely about the weather but which aren’t. Two of these are “Small Craft Warnings, Block Island to Hatteras” and “Snow Flurries Expected This Weekend in New Orleans.” The messages enable the Mafia boss to keep control of his narcotics syndicate. Holly wasn’t involved knowingly in the drug smuggling however.”

“What’s Holly like?” “She’s a wacky lady who makes a holiday out of life and who walks through it lightly. She prefers to be ‘natural’ rather than ‘normal,’ has a lifestyle full of irregularities, and has a cat with no name, whom she calls “Cat.” She drinks champagne for breakfast, waters her plants with her mixed drinks, has the head of a cow hanging on the wall of her apartment, and at her wild parties smokes long-stem cigarettes, ones which set the hats of her guests on fire. Eventually, we learn that she’s the runaway wife of a horse doctor from Tulip, Texas. Audrey Hepburn is great. So is Breakfast at Tiffany’s theme song, “Moon River.” The movie may still be playing in neighborhood theatres. You should see it.” “I’ll try to.”

“Anyway, what are you planning to do this summer?” “I’ll be working as a janitor at Narragansett Electric Company in Providence.” “How did you get that job?” “With my science project on “Hydroelectric Power from the Sea.” An executive from Narragansett Electric saw it at the Rhode Island Science Fair and wondered whether I’d like to display it at their downtown store. I said, ‘Sure.’ They set it up in their window for a couple of weeks. When I was taking it home, the executive said to let him know if he could do anything else for me. So I wrote him a letter and requested a summer job. Last summer, I worked at their Manchester Street power plant. It’s got a great view of the Providence River. Occasionally, we do some sunbathing on the plant’s roof.

“Last summer, we spent several days up there, stretched out on our stomachs so we could look down from the edge at “Willie the Whale.” Did you read about Willie in the Boston papers?” “No.” “Well, Willie was a 20-foot pilot whale who got lost. Some scientists believe that while chasing menhaden he went off course. He swam up the Providence River and drew thousands of spectators. Whales usually travel in schools but Willie was alone. For six days last July he was a celebrity in downtown Providence. He leapt out of the Providence River every few minutes with the adroitness of a porpoise. The Providence Journal wrote several front-page articles about him. Have you ever seen a whale? Not many New Englanders our age have.” “Only the skeleton of one at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. How far from the ocean is the Providence River?” “Twenty-five miles!” “Did Willie seem sick or wounded?” “No. He swam around effortlessly. His favorite swimming spot was next to the Manchester Street power plant.” “Did anyone help him?” “Yes. Two URI marine scientists attempted to lure him away from the port of Providence with underwater recordings of his voice and those of other whales’ voices. That didn’t work. Willie couldn’t decide which way was out and wouldn’t take any of their blusterous back talk. Other Rhode Islanders weren’t as considerate, however. Several men with harpoons tried to spear Willie until they were stopped by the Providence harbormaster. Fortunately, none of them was fast enough to get off an accurate shot. Also, one Providence resident jumped into the river in his underwear and tried to ride Willie. He was fined $5 for drunkenness.”

“So what happened to Willie?” “On the sixth day of cavorting in the Providence River he died.” “Did anyone do an autopsy?” “Yes. A marine biologist from Woods Hole examined the carcass. He couldn’t determine the cause of Willie’s death. However, guess what?” “What?” “The guy from Woods Hole found out that Willie was a female, one which was not fully grown but one which was old enough to vote.” “Ha!”

“So what are you going to do this summer, Audrey?” “I’ll be working at Nellie’s ice cream stand on the outskirts of Natick. That’s where I worked last summer.” Stifling a yawn while telling me this, Audrey brushed up against me. “Excuse me,” she muttered immediately. Neither of us said anything for a minute or two. That was the only lull in our five-hour chat, one which lasted from a little past midnight ’til daybreak. Then Audrey told me about her visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. where she saw some portrait paintings by Gilbert Stuart and John Singleton Copley. Around 5:30 Space said he was exhausted. All of us were. So we woke up Andy and went back to our room. The NIT Championship wasn’t until 4 p.m., but the girls’ bus to Boston left at noon. When we said goodbye to Bonnie, Claire, and Audrey, I gave Audrey a kiss — one which landed on her nose as she was turning her head. Undaunted, I asked Audrey to write down her address. She did this for me, and I told her I’d be in touch. Then Andy, Eddie, Space, and I caught some winks and went over to Madison Square Garden for the final game between PC and Canisius.

Friars seize control early in title game

At the Garden, we had trouble finding our upper-tier seats. A sellout crowd of 18,499 was on hand, the biggest throng ever for an afternoon NIT final. As we watched PC warm up in their black “away” uniforms, we participated in the pre-game chant of “Let’s go, Friars!” Canisius’ Tony Gennari scored the game’s opening basket, but Vinnie Ernst and Jim Stone brought Providence College back. The Golden Griffins never led from that point onward. Every time they tried to close a widening gap the Friars responded with team and individual efforts. Thompson, Stone, Ernst, and Flynn made a succession of electrifying shots during the first half. At the end of the half it was Providence 41, Canisius 32. With only three minutes gone in the second half, Bill O’Connor, Canisius’ talented and agile 6-5 center, got PC’s Thompson to commit his fourth foul. This could have changed the course of the game. However, Joe Mullaney switched Thompson to a corner and had Bob Kovalski, the Friars’ 6-8 sophomore forward, contain O’Connor in close. That’s where O’Connor continued to stay. “Big K” held him to six points the rest of the way. Thereafter, the Griffs seemed doomed to defeat. PC’s unusual combination of zone and man-to-man defenses caused Canisius to play totally out of sync.

Stone started a surge which put PC up 15, one during which Flynn scored on a dash, Stone dropped in two free throws, Thompson made a twisting lay-up, and Flynn hit a bomb from the baseline as well as a running one-hander. After Canisius cut the lead to 11 during a couple of minutes of frenetic pursuit, PC called a time-out and calmly regrouped. When play resumed, Ernst scored from outside, Flynn made two free throws, and Stone hit a gyrating jumper on which he was fouled. Subsequently, O’Connor made a field goal and was credited for another when Thompson was called for goaltending. Then Stone got fouled and made two more free throws. The Friars’ lead never dropped below seven. In the game’s closing minutes, the PC forces were in complete control. Not only did the Friars run the clock down effectively but Flynn, Stone, and Kovalski fired in a series of beauties, ones which brought roars of approval from Gotham’s aficionados. The final score was Providence College 81, Canisius 66.

The Friars’ 15-point win assuaged a five-point, early-January loss to the Griffs in Buffalo. Stone led all scorers with 23 points. His spectacular shooting and driving was one of the game’s highlights. Flynn had 20 on high, arching jumpers. After the game he was named tourney MVP. For the entire tournament he averaged 27.3 points per game and hit on 52.6 percent of his shots, showing that he was the equal from outside of any collegiate player. His MVP award made him the third Friar in four years to win the NIT trophy of distinction. Vinnie Ernst had gotten it in 1961, and Lenny Wilkens had gotten it in 1960. Ernst ran the Friar offense flawlessly and guarded tenaciously. He stole the ball eight times and had 10 assists. Thompson defended at his season’s best and tallied 15. Kovalski showed what a sophomore he was and notched 10. PC made 23 of 26 free throws and shot nearly 50 percent for the game. The victory was Providence’s 15th in a row and their 24th win in 28 starts. O’Connor had 22 for the game and was Canisius’ high scorer. With the triumph, Providence College became one of only three teams to capture two NIT titles.

Saturday night we had some steaks at a Tads and saw The Longest Day, a dramatization of the Allied Forces’ monumental invasion of Normandy on D-Day, 1944. On Sunday, we went to an early Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and then checked out of the Taft. It took us about an hour to leave NYC and reach the Connecticut Turnpike. We talked about basketball and girls on our way home — that is, until we approached the Rhode Island state line, where we saw clusters of cars along the Connecticut roadside. When we got into Rhode Island, more than 3,000 cars were idling on Route 6. Then we pulled into State Line Sunoco to get some gas, and the Providence College bus drove in a couple of minutes afterwards. Wanting to be part of the welcome, we decided to follow the PC bus along Route 6 for the remaining 20 miles to Providence. Through rural Foster, thousands of Rhode Islanders were parked on both sides of the highway. When we reached the town of Scituate, a state police cruiser and a caravan of 500 to 600 cars began escorting the PC bus the rest of the way into Providence.

At every major intersection, Rhode Island state troopers cut off cross traffic to let the PC caravan pass. Big crowds of Rhode Islanders were gathered along Route 6 in the center of Johnston and along Route 6 at the Providence city line. The bus stopped briefly at the latter so that Coach Mullaney, captain Ray Flynn, and forward Jim Stone could climb into the back of an open white convertible for the ride through downtown. When we reached downtown Providence, we parked on a side street and watched the bus pull up to City Hall. In front of City Hall, a crowd of 8,000 people was gathered. The throng extended from the base of City Hall to the bus terminal building on the edge of the mall. Shortly thereafter, the PC team filed onto the steps of City Hall, where they were greeted by John Chafee, governor of Rhode Island.

Then they were introduced individually by Chris Clark, radio/TV voice of the Friars and a Channel 12 sportscaster. The crowd gave each PC player an ovation, ones which were accompanied by tumultuous screams of delight. The sheer statistics of that Sunday’s celebration distinguished it as one of the biggest receptions ever given to returning heroes by the State of Rhode Island. When I dropped off Andy, Eddie, and Space near Alumni Hall on the PC campus a while later, another crowd of 6,000 PC supporters was chanting and cheering the triumphant Friars. We joined in those festivities, too. That’s how our March weekend in the spring of 1963 went. It was one of those weekends you never forget.

Epilogue

Since then, Providence College basketball teams have had more than 18 seasons with 20 or more wins, have made approximately 15 appearances in the NCAA Tournament, have been to the NCAA Final Four twice, and have had more than 20 players drafted to the NBA — the latest two being Kris Dunn and Ben Bentil in 2016. Providence College continues to play in the powerful BIG EAST Conference.

Two members of the 1963 Friars went on to positions of national prominence. One was black and one was white. One did so in sports; the other did so in politics. After being named New England Player of the Year in 1964 and then backing up Bill Russell on the Celtics for two years, John Thompson became head basketball coach at Georgetown University in 1972. During a coaching stint which spanned 27 years, he was an outspoken and opinionated advocate for minorities. His Hoyas went to the Final Four three times and won the national championship in 1984. Ray Flynn spent three terms on the Boston City Council and then was elected mayor of Boston three times. He was the first resident of “Southie” — tough South Boston — to become mayor. During his tenure as mayor, Flynn restored Boston to fiscal solvency, improved race relations among the citizenry, and made downtown developers devote some of their resources to the restoration of Boston’s deteriorating neighborhoods. In 1992, he became president of the United States Conference of Mayors. From 1993 to 1997, he served as U.S. ambassador to the Vatican. Then in 1999 he was appointed president of the Catholic Alliance, a nonpartisan organization devoted to empowering working Americans.